Types of Batten Disease

Batten disease, or Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCL), has 13 known forms. Progressions of the different forms of the disease vary (the phenotype) based on the type of genetic mutation (the genotype) and other factors. Each form is classified by the gene that causes the disorder. Each gene is called CLN (ceroid lipofuscinosis, neuronal) and given a different number designation as its subtype. The disorders generally include a combination of vision loss, epilepsy, and dementia. For more information about genetic science and a glossary of terms the US National Human Genome Research Institute provides a useful . We have collaborated with our scientific colleagues in the field of Batten disease to provide clinical summaries for as many forms of the disease as possible. We seek out and publish updated information on each type because we serve families impacted by all forms of the disease.

Batten disease, or Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCL), has 13 known forms. Progressions of the different forms of the disease vary (the phenotype) based on the type of genetic mutation (the genotype) and other factors. Each form is classified by the gene that causes the disorder. Each gene is called CLN (ceroid lipofuscinosis, neuronal) and given a different number designation as its subtype. The disorders generally include a combination of vision loss, epilepsy, and dementia. For more information about genetic science and a glossary of terms the US National Human Genome Research Institute provides a useful . We have collaborated with our scientific colleagues in the field of Batten disease to provide clinical summaries for as many forms of the disease as possible. We seek out and publish updated information on each type because we serve families impacted by all forms of the disease.

Clinical Summaries

Infantile onset and others

What is the cause?

The gene called CLN1 lies on chromosome 1. CLN1 disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both chromosomes carry mutations in the CLN1 gene, and both parents are unaffected carriers. The gene was discovered in 1995. CLN1 normally directs production of a lysosomal enzyme called Palmitoyl protein thioesterase 1 or PPT1. A deficiency of PPT1 results in abnormal storage of proteins and lipids in neurons and other cells and impaired cellular function. The cells cannot function as they should and symptoms develop.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by enzyme (PPT1) and genetic (CLN1) tests on blood samples. Occasionally a skin biopsy may be necessary. Granular osmiophilic deposits (GRODSs) are the characteristic storage body at the electron microscope level.

Does it have any alternative name?

CLN1 disease was first described in the 1970s in Finland and is sometimes called Haltia-Santavuori Disease, Infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, or INCL.

How does the disease progress?

Genotype/phenotype correlations

Classical CLN1 disease, infantile

Babies are healthy and develop normally for the first few months of life. Towards the end of the first year, developmental progress starts to slow down. Infants may have difficulty sleeping through the night and may become more restless and irritable during the day. Some infants develop repetitive hand movements and fiddling. They often become floppy and developmental skills such as walking, standing and speech are lost.

Children become less able and increasingly dependent during the toddler years. By the age of 2 years, most will have epileptic seizures and jerks. Vision gets worse until they are no longer able to see. From about the age of three years, children are completely dependent, unable to play, feed themselves, sit independently or communicate. They may need a feeding tube and their arms and legs usually become stiff. Some children get frequent chest infections. Most affected children die in early to mid-childhood.

CLN1 disease, juvenile onset

Some children with CLN1 abnormalities develop the disease after infancy—around age 5 or 6—and have slower disease progression. Affected children may live into their teenage years. Others may not develop symptoms until adolescence and may live into adulthood. CLN1 disease, variant late infantile and adult types. A wide variety of age at symptom onset and disease progression is seen with mutations in CLN1.

Scientific Posters for CLN1

A New and Effective Target for Infantile Batten Disease

Shyng, Nelvagal, Dearborn, Cooper, & Sands

Gene Therapy for Infantile NCL

Gray & Rozenberg

Late-infantile

What is the cause?

The gene called CLN2 lies on chromosome 11. CLN2 disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both chromosomes carry mutations in the CLN2 gene, and both parents are unaffected carriers. The gene was discovered in 1998. CLN2 normally directs production of a lysosomal enzyme called tripeptidyl peptidase1 or TPP1. A deficiency of TPP1 results in abnormal storage of proteins and lipids in neurons and other cells and impaired cellular function. The cells cannot function as they should and symptoms develop.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by enzyme (TPP1) and genetic (CLN2) tests on blood samples. Occasionally a skin biopsy may be necessary. Curvilinear bodies (CVB) are the characteristic storage body at the electron microscope level.

Does it have any alternative name?

CLN2 late infantile disease is sometimes called Jansky-Bielschowsky Disease or late infantile NCL (LINCL).

How does the disease progress?

Children are healthy and develop normally for the first few years of life. Towards the end of the second year, developmental progress may start to slow down. Some children are slow to talk. The first definite sign of the disease is usually epilepsy. Seizures may be drops, vacant spells or motor seizures with violent jerking of the limbs and loss of consciousness. Seizures may be controlled by medicines for several months but always recur, becoming difficult to control. Children tend to become unsteady on their feet with frequent falls and gradually skills such as walking, playing and speech are lost. Children become less able, and increasingly dependent. By 4-5 years the children usually have myoclonic jerks of their limbs and head nods. They may have difficulties sleeping and become distressed around this time, often for no obvious reason. Vision is gradually lost. By the age of 6 years, most will be completely dependent on families and careers for all of their daily needs. They may need a feeding tube and their arms and legs may become stiff. Some children get frequent chest infections. Death usually occurs between the ages of 6 and 12 years (but occasionally later).

CLN2 disease, later onset

Some children with CLN2 abnormalities develop the disease later in childhood —around age 6 or 7—and have slower disease progression. In later-onset CLN2 disease, loss of coordination (ataxia) may be the initial symptom. Affected children may live into their teenage years.

The TTP1 deficiency in atypical CLN2 can present as symptoms of ataxia and cerebellar atrophy but the individual does not necessarily develop seizures or vision loss. This example of atypical CLN2 is referred to as SCAR7, or spinocerebellar ataxia autosomal recessive 7.

Treatment

CLN2 is currently the only form of Batten disease that has an FDA approved treatment. The enzyme replacement therapy, Brineura® (cerliponase alfa), was created by BioMarin and was approved by the FDA in April 2017. It was approved to slow loss of ability to walk or crawl (ambulation) in symptomatic pediatric CLN2 Batten disease patients 3 years of age and older. It is available commercially through several hospitals across the U.S. For more information about this treatment visit https://www.brineura.com.

There are ongoing efforts for CLN2 treatments in both gene therapy and small molecule therapy. The work in scientific research for further treatments and a cure for all forms of Batten disease continues. If you would like to talk to us about ongoing research, please contact us at info@bdsra.org.

Juvenile

What is the cause?

The gene called CLN3 lies on chromosome 16 and was discovered in 1995. CLN3 disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both chromosomes carry mutations in the CLN3 gene, and both parents are unaffected carriers. This gene codes for a transmembrane protein. The nerve cells cannot function as they should and symptoms develop.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by genetic (CLN3) tests on blood samples. Occasionally a skin biopsy may be necessary.

Does it have any alternative name?

At the beginning of the 20th century Dr. Frederick Batten described a group of disorders that now bear his name. Over time it was discovered that there were several types of the disease with similar but distinct features and ages at onset of symptoms: infantile, late infantile, juvenile, and adult. CLN3 disease is often called Batten disease, or Spielmeyer- Sjogren-Vogt disease.

How does the disease progress?

Children are healthy and develop normally for the first few years of life. The first sign of the disease is usually a gradual loss of vision between 4 and 7 years of age. This may be noticed first at nursery or at school. Vision changes rapidly over 6 to 12 months initially but children retain some awareness of color and light/dark until later. By the end of primary school, children are beginning to show some difficulties with concentration, short-term memory and learning. Many are still able to attend mainstream school but may need extra learning support in the classroom. The next stage of the disease starts with the onset of epileptic seizures (average age of onset of seizures is 10 years). Often the first seizures are motor seizures with violent jerking of the limbs and loss of consciousness. Seizures may be controlled by medicines for several months or years, but always recur, eventually becoming difficult to control completely. The pattern of seizures may change over time and other seizure types may evolve, such as vacant spells and episodes of partial awareness with fiddling and muddled speech.

During the teenage years children tend to slowly become more unsteady on their feet. At around the same time speech may become repetitive and gradually more difficult to understand. Not uncommonly children become anxious and tend to worry. Some feel things, hear voices or see things that are unreal. Teenagers become less able and increasingly dependent. The course of the disease is extremely variable even for children from the same family. The teenagers and young adults are much more able some days than others, especially in terms of mobility, communication and feeding skills. The disease progresses with periods of stability which may last months or years alternating with periods of deterioration lasting several months which may be triggered by intercurrent illness. Death usually occurs between the ages of 15 and 35 years (but occasionally later).

Scientific Posters for CLN3

Neuroinflammation in Juvenile Batten Disease and the Role of an Anti-inflammatory Treatment – Kielian, Kakulavarapu, Bosch, Aldrich, Burkovetskaya, & Karpuk

Gene Therapy for the Eye- Mole Laboratory

Pediatric Storage Disorders Lab (Jon Cooper): New lessons form out work on Batten disease – Cooper

Variant Late Infantile

What is the cause?

This disease is caused by problems with lysosomal protein called CLN5, whose function is unknown. The CLN5 gene is located on chromosome 13.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by histological and genetic tests on blood samples. A skin biopsy may be necessary and the abnormal storage material takes on a mixed appearance with granular osmiophilic deposits (GRODS), curvilinear bodies (CVB), rectilinear profiles (RLP), and/or fingerprint profiles (FPP). The appearance of the storage material can guide the genetic diagnostic tests in some cases.

Genetic testing is recommended to look for the exact mutation or mistake in the CLN5 gene. A blood or saliva sample will be taken to extract DNA from the cells for the test.

Does it have any alternative name?

CLN5 disease, variant late-infantile may also be referred to as variant late-infantile CLN5 disease. It has previously been described as Finnish, Turkish, Indian, or Mediterranean Variant NCL, alongside Variant Late Infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (LINCL); though was more commonly known as Variant Late-Infantile Batten Disease.

How does the disease progress?

Genotype/phenotype correlations

CLN5 disease, Variant Late-Infantile

Children progress normally for the first few years of life before they start losing skills and develop behavior problems. Seizures and myoclonic jerks begin usually between ages 6 and 13. Vision deteriorates and is eventually lost. Children have learning disabilities and problems with concentration and memory. Some may need a feeding tube. Most children with CLN5 live into their late childhood or teenage years.

CLN5 posters from a recent BDSRA Family Conference Scientific Poster Session

Batten Animal Research Network (BARN): Varient Infantile Batten Disease – Palmer

Neurogenetics Lab: The CLN5 (aka CLN9) and CLN8 proteins as Ceramide Synthases or Their Modulators – Boustany, Haddad, Khoury, Daoud, Mousallem, & Alzate

Variant late-infantile onset and adult onset

What is the cause?

This disease is caused by problems with lysosomal protein called CLN6, whose function is unknown. The CLN6 gene is located on chromosome 15.

What is the cause?

The gene CLN6, located on chromosome 15, directs the production of the protein CLN6, also called linclin. The protein is found in the membranes of the cell (most predominantly in a structure called the endoplasmic reticulum). Its function has not been identified.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by histological and genetic tests on blood samples. A skin biopsy may be necessary and the abnormal storage material takes on a mixed appearance with granular osmiophilic deposits (GRODS), curvilinear bodies (CVB), rectilinear profiles (RLP), and/or fingerprint profiles (FPP). The appearance of the storage material can guide the genetic diagnostic tests in some cases.

Genetic testing is recommended to look for the exact mutation or mistake in the CLN6 gene. A blood or saliva sample will be taken to extract DNA from the cells for the test.

Does it have any alternative names?

CLN6 disease, variant late-infantile was one of the first variant types of Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis (NCLs) to be identified and was originally termed early Juvenile Batten disease.

How does the disease progress?

Genotype/phenotype correlations

CLN6 disease, Variant Late-Infantile

Symptoms vary among children, but typically start after the first few years of life and include developmental delay, changes in behavior, and seizures. Children eventually lose skills for walking, playing, and speech. The also develop myoclonic jerks, problems sleeping, and vision loss. Most children with CNL6 die during late childhood or in their early teenage years.

CLN6, Adult Onset

Also known as Kufs’ disease Type A, this form of CLN6 disease shows signs in early adulthood that include epilepsy, inability to control muscles in the arms and legs (resulting in a lack of balance or coordination, or problems with walking), and slow but progressive cognitive decline.

Variant late-infantile onset

What is the Cause?

This disease is caused mutations in the CLN7 gene, is located on chromosome 4, which produced the protein MFSD8. MFSD8 a member of a protein family called the major facilitator superfamily. This superfamily is involved with transporting substances across the cell membranes.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by histological and genetic tests on blood samples. A skin biopsy may be necessary and the abnormal storage material takes on a mixed appearance with granular osmiophilic deposits (GRODS), curvilinear bodies (CVB), rectilinear profiles (RLP), and/or fingerprint profiles (FPP). The appearance of the storage material can guide the genetic diagnostic tests in some cases.

Genetic testing is recommended to look for the exact mutation or mistake in the CLN7 gene. A blood or saliva sample will be taken to extract DNA from the cells for the test.

Does it have any alternative names?

CLN7 disease, variant late-infantile may also be referred to as variant late-infantile CLN7 disease, alongside Variant Late Infantile Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis; though was more commonly known as Variant Late-Infantile Batten Disease.

How does the disease progress?

Genotype/phenotype correlations

CLN7 disease, Variant Late-Infantile

Developmental delays begin after a few years of normal development. Children usually develop epilepsy between the ages of 3 and 7 years, along with problems sleeping and myoclonic jerks. Children begin to lose the ability to walk, play, and speak. A rapid advancement of symptoms is seen between the ages of 9 and 11. Most children with the disorder live until their late childhood or teenage years.

CLN7 posters from a recent BDSRA Family Conference Scientific Poster Session

Variant Infantile Batten Disease – Storch

Synaptic Changes in Neuronal Ceriod Lipofuscinosis – Tuxworth, O’Hare, & Tear

EPMR and Late Infantile Variant

What is the cause?

The gene called CLN8 lies on chromosome 8. CLN8 disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both chromosomes carry mutations in the CLN8 gene, and both parents are unaffected carriers. The gene was discovered in 1999. CLN8 normally directs production of a protein that is embedded in internal cell membranes. The cells cannot function as they should and symptoms develop.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by histological and genetic (CLN8) tests on blood samples. A skin biopsy may be necessary. The characteristic storage bodies at the electron microscope level often show a mixture of fingerprint profiles (FPP) and curvilinear bodies (CVB).

How does the disease progress?

Genotype/phenotype correlations

CLN8 disease, Epilepsy with Progressive Mental Retardation (EPMR) or Northern Epilepsy

This disease is caused by mutations in CLN8 but has seldom been described outside Scandinavian countries. Symptoms usually start between the ages of 5 and 10 years, with seizures. Cognitive decline occurs at around the same time. Seizure frequency increases until puberty. Cognitive deterioration is more rapid during puberty. Behavioral disturbances can occur, eg: irritability, restlessness, inactivity and these features may continue into adulthood. Epilepsy is partially responsive to treatment. The number of seizures decreases spontaneously after puberty, even with no change in treatment, and by the second-third decade they become relatively sporadic. Cognitive decline continues and in some cases loss of speech has been reported. Motor function is also impaired. In a number of cases, visual acuity is reduced (without evidence of retinal degeneration). The disease has a chronic course and survival to the sixth or seventh decade has been reported. EPMR is very unusual amongst the NCLs of childhood onset in this respect.

CLN8 disease, variant late infantile

All children have developmental delay before the onset of symptoms at 2 -7 years of age: myoclonic seizures and an unsteady gait are commonly the initial symptoms; other seizures follow soon after. Cognitive decline and visual impairment usually occur. Behavioral abnormalities are frequent. Rapid disease progression with loss of cognitive skills is observed over two years from the time of diagnosis. By the age of 8-10 years severe deterioration of neurological and cognitive skills is apparent together with medication resistant epilepsy. Spasticity, dystonic posturing, tremors, and other extrapyramidal signs are also observed commonly. In the second decade of life children are unable to walk or stand without support. The life-expectancy of children affected by this disease is not yet known. The eldest patients known are now in their second decade, and their general health remains good.

CLN8 posters from a recent BDSRA Family Conference Scientific Poster Session

Basic Research on the neuropathology of CLN8; Varient Infantile Batten Disease – Kuronen, Lehesjoki, & Kopra

What’s New on CLN8 in Latin America? – Pesaola, Cismondi, Guelbert, Kohan, Carabelos, Alonso, Pons, Oller-Ramirez, Noher de Halac

Congenital, neonatal and late infantile

What is the cause?

This is a very rare form of NCL and only a small number of cases have been written about. There may be undiagnosed cases. This disease is caused by mutations in a gene called Cathepsin D also called CLN10, which lies on chromosome 11. CLN10 disease is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both chromosomes carry mutations in the CLN10 gene, and both parents are unaffected carriers. The gene was discovered in 2006. CLN10 normally directs production of a lysosomal enzyme called cathepsin D. If no enzyme is produced, symptoms start very early in life, or even before birth. If some enzyme is working, symptoms develop later and disease progression is slower.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnosis is usually made by enzyme (CTSD) and genetic (CLN10) tests on blood samples. Occasionally a skin biopsy may be necessary. Granular deposits are the characteristic storage body at the electron microscope level.

How does the disease progress? Genotype/phenotype correlations CLN10 disease, congenital

Seizures occur before birth. In the newborn period the babies have refractory seizures and apnoeas. Babies may die within the first weeks of life.

CLN10 disease, late infantile

Some children with mutations in CLN10 have a later onset of symptoms and slower disease progression, like variant late infantile NCL. Children become unsteady, develop seizures and visual impairment. Later they lose skills.

CLN10 posters from a recent BDSRA Family Conference Scientific Poster Session

Juvenile Onset Presentation of Neuronal Ceroid Lipofuscinosis Due to Mutations in CTSD – Currow, Spaeth, Sisk, & Hallinan

Adult NCL is very rare although affected families have been described from several different countries.

Adult NCL has often been called Kufs disease and doctors recognize two main types – called type A and type B. Unlike the childhood NCLs, vision is not affected in either type. In some families inheritance is recessive but in others a dominant inheritance pattern is seen. Until the genetic basis for the adult NCLs is fully understood, diagnosis is usually dependent on a brain biopsy. It is emerging that several genes can cause adult onset NCL diseases, some of which have been presented at this meeting. Type A presents in early adulthood with a progressive myoclonic epilepsy, ataxia and slow cognitive deterioration over many years. Type B usually presents with an early dementia or evolving movement disorder. Mild mutations in childhood NCL genes may also cause NCL disease with delayed age of onset and slow disease progression but vision is generally affected and abnormal storage is seen more reliably in peripheral tissues.

Adult onset posters from a recent BDSRA Family Conference Scientific Poster Session

Mole Laboratory: Adult Batten Disease – Mole, Bond, Vieira, Marotta, Holthaus, Ridier, Warrier, Brown

Adult Batten Disease: New Genes, Better Diagnosis – Smith, Dahl, Damiano. Bahlo & Berkovic

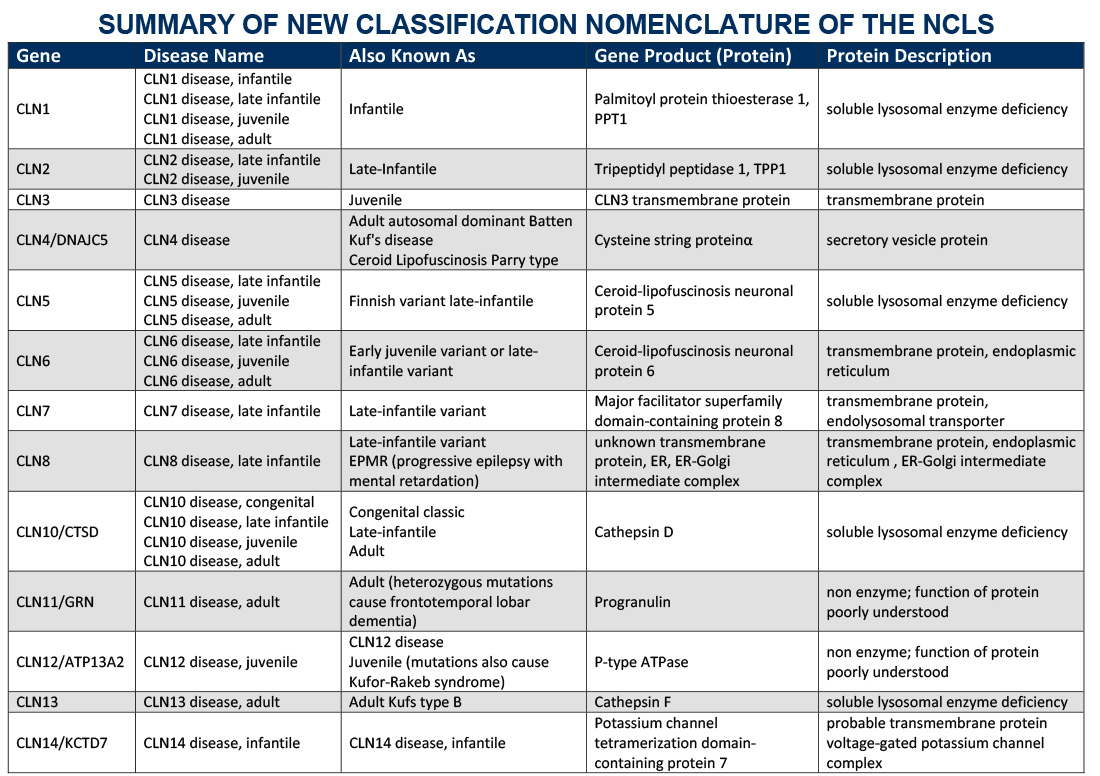

Gene Table

Below is a table outlining the gene symbol and protein associated with specific disease types was adapted by the BDSRA from Dr. Sara Mole and Dr. Ruth Williams, NCL2012 Abstract Book (2012) and is available for download. Summary of New Classification Nomenclature of the NCLs .

Diseases listed in the gene table are all autosomal recessive unless noted. It is possible that further cases of later onset e.g. CLN2 disease, adult, or those with atypical progression, e.g. CLN3 disease, juvenile, will yet be recognized.