The power of advocacy can be defined by Tracy VanHoutan’s work.

VanHoutan, husband to Jennifer and father to Noah, Laine, Emily, and Colette, was described by former BDSRA Executive Director Margie Frazier as a “driving force” behind Brineura, described by its manufacturer BioMarin as, “indicated to slow the loss of ambulation in symptomatic pediatric patients 3 years of age and older with late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2 (CLN2), also known as tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (TPP1) deficiency.”

It’s the first enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) to be directly administered into the fluid of the brain and became FDA-approved six years ago. It’s the first and so far, only FDA-approved treatment for any form of Batten disease.

Although Noah and Laine both had CLN2 Batten disease and passed away in 2016 and 2018, respectfully, they never got to receive Brineura.

Their stories along with VanHoutan’s relentless advocacy helped pave the way for this milestone – leaving more time for CLN2 families with their affected children.

“So many people helped,” VanHoutan said. “We were just a piece of it. We stepped in where we could. There were hundreds and hundreds of people that had their finger in making Brineura a reality.”

The road to the VanHoutan family’s first Batten diagnosis is similar to those of fellow Batten families – an uncharted road of questions, seizures, motor loss, misdiagnosis, uncertainty, and heartbreak.

Noah was diagnosed with CLN2 Batten disease on March 17, 2009, after numerous doctor’s appointments in Chicago, Washington University in St. Louis, and Duke University seeking an explanation for the seizures, balance, and speech issues he began suffering in December 2007. He was originally diagnosed with epilepsy and Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome.

A few months after his diagnosis, Emily and Laine, Noah’s twin sisters, were tested with Laine’s test coming back positive for CLN2. They were three and a half years old.

The VanHoutan Family (Pictured back from left: Jennifer, Colette, Tracy. Pictured front from left: Noah, Laine, Emily. Photo provided by Tracy VanHoutan).

From there, the VanHoutan family embarked on their Batten journey with a focus on raising funds for research: Founding Noah’s Hope (which later partnered with Hope 4 Bridget), joining the BDSRA Board of Directors, sharing their story, attending the NCL Conference in Hamburg, Germany, and Rare Disease Week on Capitol Hill, organizing numerous fundraisers, and presenting to the FDA.

Name any type of advocacy work and there’s a great chance VanHoutan has done it.

“I was looking at everything I could do,” VanHoutan said. “You don’t have to know everything, but if you get the opportunity, there are people who will come and help you do something very impactful.”

That advocacy and fundraising continue today.

Noah’s Hope/Hope 4 Bridget still helps fund research, focusing on early-stage, high-risk projects that have an opportunity to have a significant impact, as well as developing tools needed by the research community such as animal models, biomarkers, and natural history studies, according to VanHoutan.

These research funds are much-needed in what’s become an even more challenging landscape when it comes to the science and research behind Batten disease and rare diseases in general – even with Accelerated Approval Pathways in place and the Orphan Drug Act signed into law by President Ronald Reagan 40 years ago.

In a report released in September 2022, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) raised concern over accelerated approval pathway with its key takeaway being: “More than one-third of accelerated approval drug applications with incomplete confirmatory trials are past their trials’ original planned completion dates, including four that are more than 5 years past those dates.”

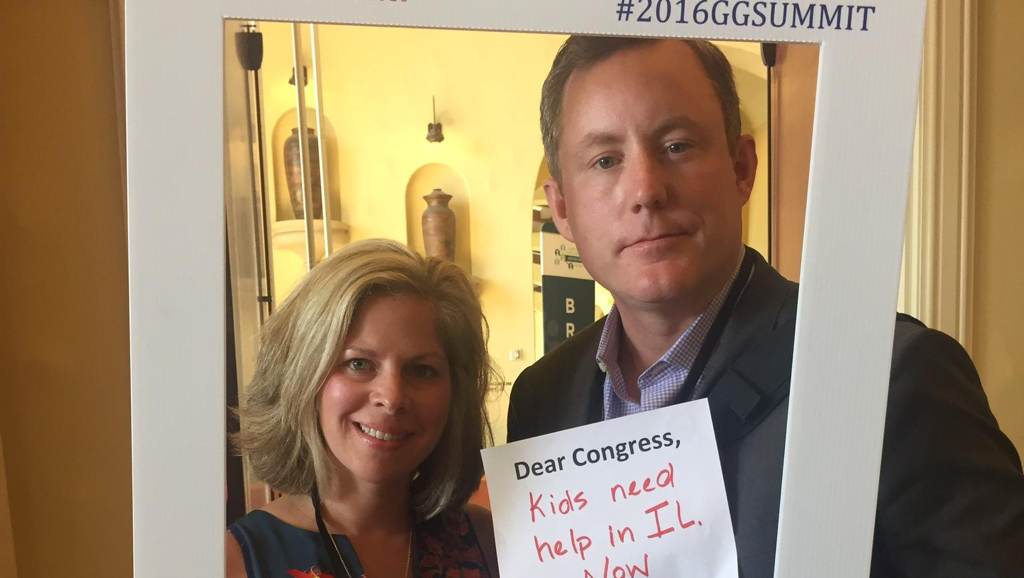

Tracy and Jennifer VanHoutan have attended countless conferences and advocacy events. Here they are pictured at the 2016 Global Genes RARE Patient Advocacy Summit (Photo provided by Tracy VanHoutan).

But that’s not to say these Accelerated Approval Pathways and the Orphan Drug Act haven’t been effective at all.

According to the EveryLife Foundation’s website, the Orphan Drug Act has resulted in the development and approval of approximately 700 new drugs and biologics for rare diseases.

“It’s an encouraging statistic,” VanHoutan said. “There’s a lot of work to do, but it’s a good start. The Orphan Drug Act was a very important piece of legislation…we hope to continue to be able to build on it.”

And the OIG’s 2022 report did find that drug applications granted accelerated approval by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) have steadily increased.

“Since the accelerated approval pathway began in 1992, drug applications granted accelerated approval by FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) have steadily increased—with 278 approved between 1992 and December 31, 2021. One-quarter of these approvals (70 of 278) occurred in 2020 and 2021,” the report said.

In 2021, there were at least 12 clinical trials related to Batten disease in the works, but by April 6, 2023, only half of those trials are active – two of which moved abroad.

The latter was an issue prior to Brineura’s clinical trial stages.

Testing in mice and dogs as well as monkey toxicology results were performed. But the FDA wanted to see additional studies that would’ve further delayed the program, while the exact same package was quickly approved for a clinical trial in Europe.

“When we started to look at what it would take to get a treatment, it became apparent pretty quickly that Noah would likely never receive a treatment, but we thought there might be a chance for Laine if we could move things on,” VanHoutan said. “When this delay from the FDA came, that 100% sealed my daughter’s fate. She would never get the chance to be considered for a clinical trial.”

The delay led to a passionate presentation by VanHoutan at the 2013 Rare Disease Congressional Caucus that year.

“When I went to this Congressional Caucus meeting, I was quite upset because I knew there were other families that had been diagnosed a month, three months, six months, nine months after us that might miss out on this shot too,” VanHoutan said.

“I had to come to terms with what was going to happen with Noah and Laine, but these were families I knew from conference, they were friends. And to know that it was so close and that these kids might not get the opportunity too, that was too much.”

The trial began in Europe and eventually, the FDA allowed the trial to begin in the United States. The European Data was used in conjunction with the U.S. data for the product to finally be approved.

VanHoutan sees the same song and dance today with gene therapy clinical trials for Batten disease earning approval abroad and not in the United States. This has again led to more U.S. patients not having the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial and for VanHoutan and others, growing frustration after spending years raising awareness and funds for research.

“Here we are nine and a half years later, and we can’t get gene therapy trials started here in the U.S. either,” VanHoutan said. “There should be some flow back here, where we actually get these trials to start here in the U.S., and I understand the FDA has a challenging job.”

“I hear a lot of talk, but I don’t see a lot of walk,” VanHoutan added.

The VanHoutan family attended the 2022 BDSRA Annual Family Conference in Cleveland, OH. A memorial for those who’ve passed away from Batten disease was held on the morning of the conference’s final day (Photo by Ira Graham III Photography & Films).

The VanHoutan family will continue to serve and advocate for the Batten community with goals of developing more meaningful treatments and perhaps one day – a cure.

But thanks to VanHoutan’s work and countless others, Brineura continues to make a difference for CLN2 families everywhere. Although Noah and Laine weren’t able to receive it, they will forever serve as the heartbeat for CLN2 families and the relationships the VanHoutan family continues to foster.

“It’s bittersweet, but it’s mostly sweet,” VanHoutan said. “It’s pretty special when we get to see these kids at conference and see how they’re doing, catch up on how their year was, and see that they’re not taking as severe of a path as our kids did. It’s not without tears. There are a few sad ones, but there are more happy ones to see that these parents get more time with their kids.”